An ordinary day of bombings on the Po Valley

by Paolo A. Dossena

by Paolo A. Dossena

The Mallory Major Operation

The Mallory Major campaign, named after its architect, Major Mallory, aimed at the destruction of all bridges and pontoons across the Po River and its tributaries. The operation began on the morning of 12 July 1944.

From the Protectorate to the Po Valley

The trains left the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia between 23 and 25 May 1944, and followed the railway line to northern Italy (Pilsen/Plzeň, Munich, Innsbruck, Brenner Pass, Treviso, Verona). (1) They arrived at the respective destinations between 27 and 29 May. (2)

On 28 May, at the train stop in Varese, the second Czech desertion (another soldier had already fled) took place when private Antonín Rottrekl jumped out of a wagon. (3)

The Government Army soldiers were forbidden to mail letters home for six weeks due to security reasons. Surveillance was strict.

The Protectirate Government Army (Regierungstruppe) was composed of about 7,000 men and 200 officers of Czech ethnicity. (4) The Czechs would be used for guard duties: the Po River bridges, railways and airports (the Po Valley is the same as Continental, northern Italy, north of the northern Apennine range). Here, together with German female helpers and German and Italian Flak (the German Anti-aircraft Defences) soldiers, they would be massacred by the American Mallory Major bombing operation.

On 28 May, at the train stop in Varese, the second Czech desertion (another soldier had already fled) took place when private Antonín Rottrekl jumped out of a wagon. (3)

The Government Army soldiers were forbidden to mail letters home for six weeks due to security reasons. Surveillance was strict.

The Protectirate Government Army (Regierungstruppe) was composed of about 7,000 men and 200 officers of Czech ethnicity. (4) The Czechs would be used for guard duties: the Po River bridges, railways and airports (the Po Valley is the same as Continental, northern Italy, north of the northern Apennine range). Here, together with German female helpers and German and Italian Flak (the German Anti-aircraft Defences) soldiers, they would be massacred by the American Mallory Major bombing operation.

‘ìl gamba ‘d légn’ (Wednesday, 12 July 1944)

The Piacenza air raid siren was sounded every night, so that, in the end, people gave up fleeding to the cellars and stayed in bed (testimony by Ms Anna Molinari).

In the early morning of Wednesday 12 July, Italian soldiers from the Farnese Palace depot company, and local workes, joined the local bridges by a stream tram which in the Piacenza ‘dialect’ was known as ‘ìl gamba ‘d légn’ (wood leg) or as ‘’l bò negàr’ (the black ox). The bridges were guarded by German soldiers and by members of the 3rd Czech Battalion.

At 7:30 a.m., the Italian soldiers and workers and the OT were reparing a bombed communication route next to the bridges, when the German anti-aircraft position gave the alarm. (5) The Italians fled the bridges, so did the Czechs and German soldiers. (6) Then, as private Ferdinando Arisi would later witness, they all heard an ‘idescribable roar’, and while the ears of the survivors were aching, the pressure wave had bent the branches of the trees. A second, worse, attack came soon afterwards. After the two bombings, while the survivors were congratulating each other, the American airplanes came back and machine-gunned them.

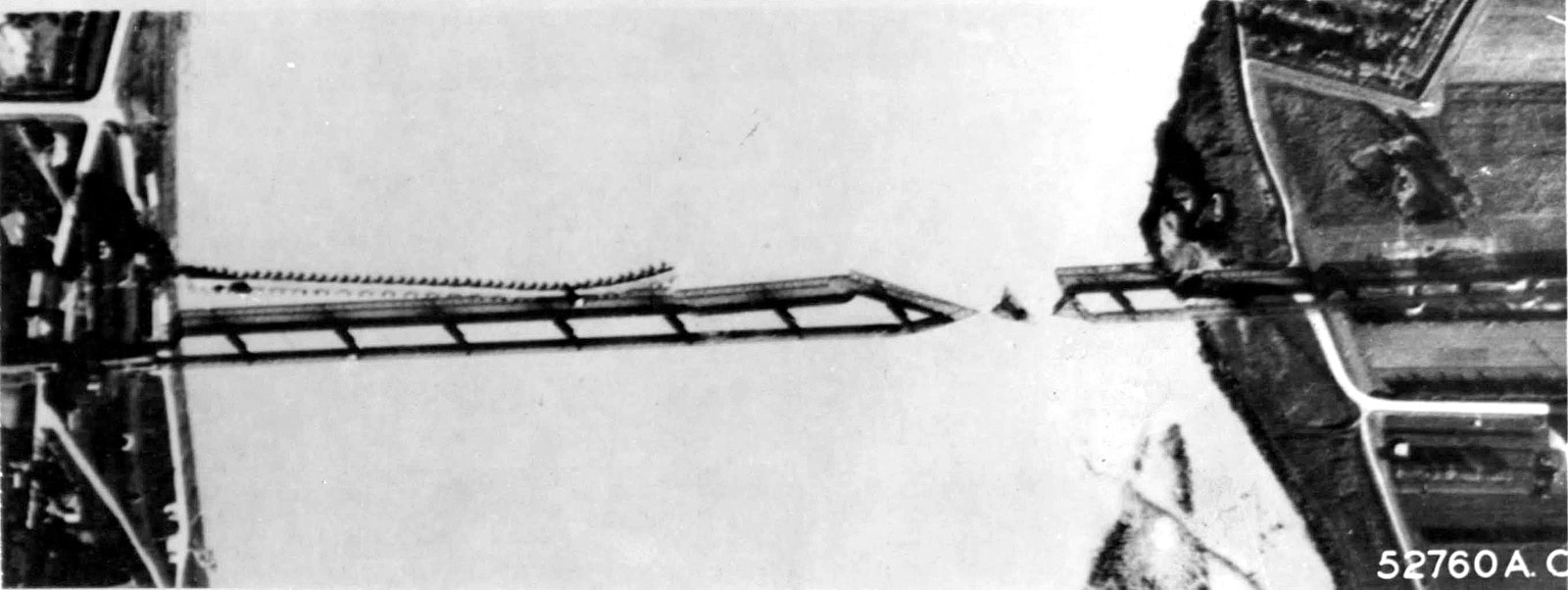

The road bridge had been destroyed during the first attack of that day, while the railway bridge would be repeatedly bombed and would be finally made completely unusable during the following raids. (7)

In the early morning of Wednesday 12 July, Italian soldiers from the Farnese Palace depot company, and local workes, joined the local bridges by a stream tram which in the Piacenza ‘dialect’ was known as ‘ìl gamba ‘d légn’ (wood leg) or as ‘’l bò negàr’ (the black ox). The bridges were guarded by German soldiers and by members of the 3rd Czech Battalion.

At 7:30 a.m., the Italian soldiers and workers and the OT were reparing a bombed communication route next to the bridges, when the German anti-aircraft position gave the alarm. (5) The Italians fled the bridges, so did the Czechs and German soldiers. (6) Then, as private Ferdinando Arisi would later witness, they all heard an ‘idescribable roar’, and while the ears of the survivors were aching, the pressure wave had bent the branches of the trees. A second, worse, attack came soon afterwards. After the two bombings, while the survivors were congratulating each other, the American airplanes came back and machine-gunned them.

The road bridge had been destroyed during the first attack of that day, while the railway bridge would be repeatedly bombed and would be finally made completely unusable during the following raids. (7)

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Above and below: American documents referring to the 12th July 1944 attacks (320th Bombardment Group)

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

Casalmaggiore, Cremona (12 July, morning)

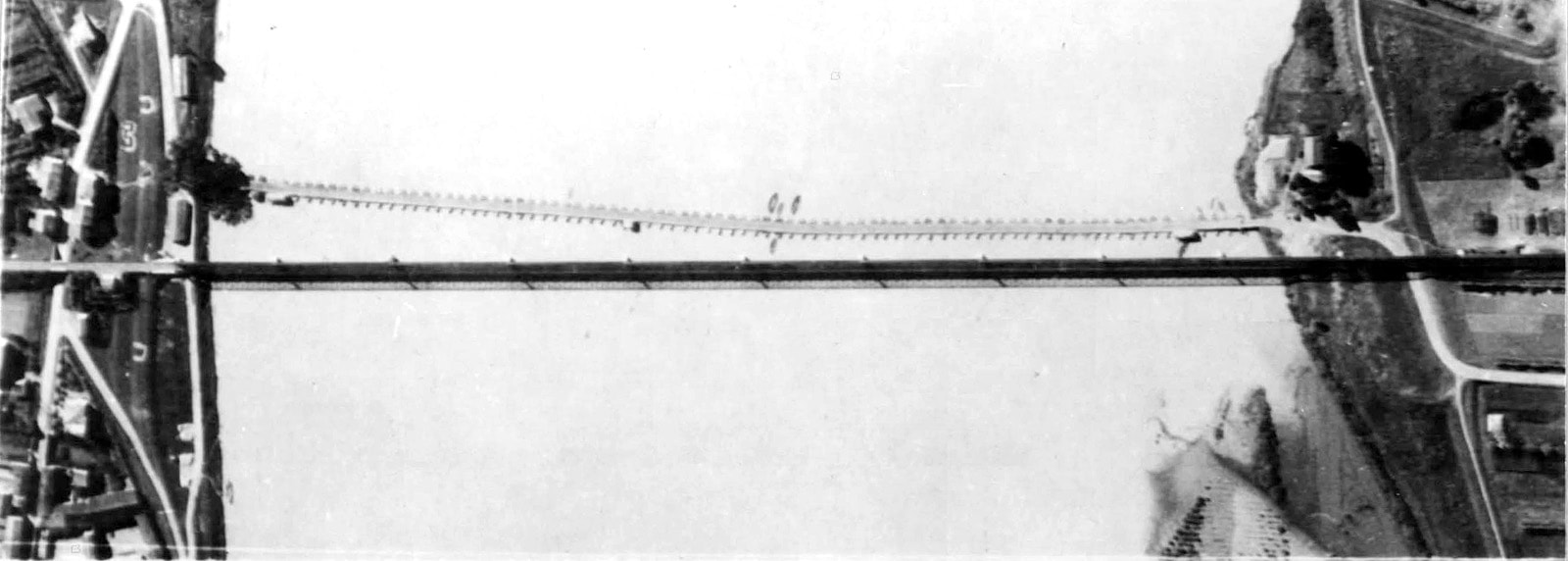

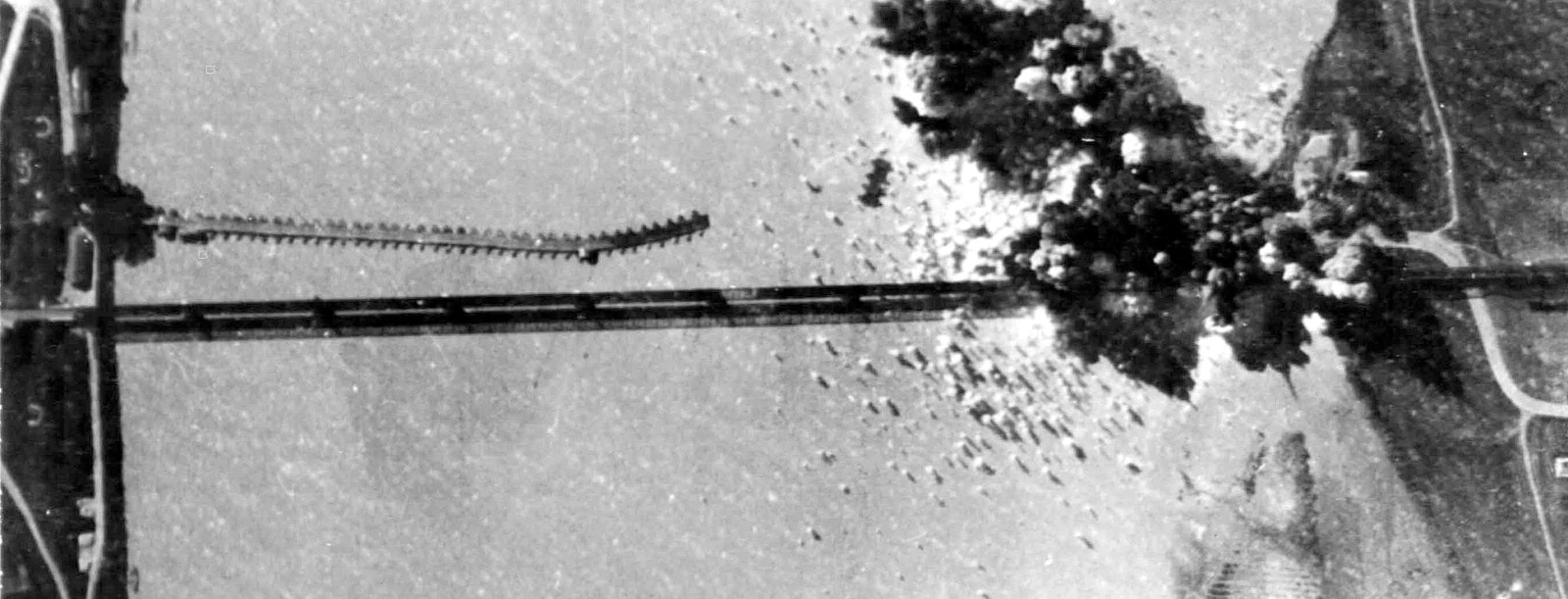

Meanwhile, on that same morning, between 9:15 and 9:31 a.m., a group of American B-26 bombers led by Captain Nunkalee attacked the Casalmaggiore (Cremona) Railway Bridge, as it is readable on the military report documenting the raid: ‘Two runs were made on the target by the second Squadron’ (9:15 and 9:31), ‘which was not in position to drop on the first run.’

The B-26 aircrafts dropped 63 Demolition bombs, and ‘The South end of the bridge received two excellent patterns of bombs.’ (8)

Immediately afterwards, at 9:49 a.m., 24 American B-26 aircrafts, led by Colonel A. A. Woolridge, raided the Cremona Bridges, which survived the attack because the German and Czech (4th Battalion) soldiers released a smokescreen. (9)

The B-26 aircrafts dropped 63 Demolition bombs, and ‘The South end of the bridge received two excellent patterns of bombs.’ (8)

Immediately afterwards, at 9:49 a.m., 24 American B-26 aircrafts, led by Colonel A. A. Woolridge, raided the Cremona Bridges, which survived the attack because the German and Czech (4th Battalion) soldiers released a smokescreen. (9)

The Sermide Czech Community, Ostiglia-Revere and Ferrara (12 July, morning)

Just a few minutes afterwards, at 10:18 a.m., the Sermide pontoon was attacked as well. This raid was conducted by other US units (445th, 446th, 447th and 448th Squadrons from the American 12th Air Force).

Subsequently, at 10.27 a.m., the same units bombed the Ostiglia-Revere bridges too.

This area, (Sermide/Ostiglia-Revere) was held by the Czech 4th Battalion, which, also managed the Viadana ferries. (10)

In this zone, the Government Army soldiers found a group of Czech individuals and families (Potuccek, Pospisek, Vinduska) whose men were skilled and appreciated technicians who worked for the local sugar refinery. Two of these Slavic gentlemen, Mr. Pospisek and Mr. Vinduska, would be killed, together with several Sermide civilians, during a subsequent wave of bombings in late February 1945. However, their descendants still live in Sermide. (11)

Still on that morning, the Ferrara Road Bridge was spared a first attack by the 340th Bombardment Group due to an effective smoke screen. Meanwhile, other aicrafts from the 340th Bombardment Group launched a second mission on Ferrara, which met ‘excellent results’. (12)

Subsequently, at 10.27 a.m., the same units bombed the Ostiglia-Revere bridges too.

This area, (Sermide/Ostiglia-Revere) was held by the Czech 4th Battalion, which, also managed the Viadana ferries. (10)

In this zone, the Government Army soldiers found a group of Czech individuals and families (Potuccek, Pospisek, Vinduska) whose men were skilled and appreciated technicians who worked for the local sugar refinery. Two of these Slavic gentlemen, Mr. Pospisek and Mr. Vinduska, would be killed, together with several Sermide civilians, during a subsequent wave of bombings in late February 1945. However, their descendants still live in Sermide. (11)

Still on that morning, the Ferrara Road Bridge was spared a first attack by the 340th Bombardment Group due to an effective smoke screen. Meanwhile, other aicrafts from the 340th Bombardment Group launched a second mission on Ferrara, which met ‘excellent results’. (12)

The German Capacity of Improvisation

Actually, two smokescreen generators were installed on both ends of the Cremona Brige, while there were no anti-aircraft batteries. (13) In spite of the great shortage of ground weapons and air power, the Germans saved a lot of situations thanks to their capacity of improvisation. (14)

As a matter of fact, the German and Czech ground troops had no air cover. Among the rare challenges by the Luftwaffe (the aerial warfare branch of the German Armed Forces), two came on 12 and 13 July, when German aircrafts counter-attacked the American pilots south of Ferrara. (15)

As a matter of fact, the German and Czech ground troops had no air cover. Among the rare challenges by the Luftwaffe (the aerial warfare branch of the German Armed Forces), two came on 12 and 13 July, when German aircrafts counter-attacked the American pilots south of Ferrara. (15)

The three photograph above show the Casalmaggiore Po Bridges before, during and after the 12 July 1944 bombardment (source: USAAF)

Casalmaggiore, Cremona, Ferrara (12 July, afternoon)

In the afternoon, at 6:48 p.m., other 33 B-26 American aircrafts, led by Captain Probasco, carried out a second attack on the Casalmaggiore Railway Bridge. According to the Allied report, ‘One Squadron’s bombs landed in the center of the bridge in a good pattern, soaring probable direct hits; another Squadron hit the South approaches; a few bombs landed over to the West’. (16)

Almost immediately after this bombing, at 6:53 p.m., another wave of B-26 American aircrafts (319th Bombardment Group), led by Colonel J. R. Holzapple, dropped 143 bombs on the Cremona railways bridge, which was clear of smoke. (17) The target was hit and severely damaged, but not destroyed. (18) Consequently, Colonel Holzapple ordered a return the next day to make sure the objective was destroyed. (19) The 319th Bombardment Group’s policy was now to revisit a target repeteadly until when the objective was totally destroyed.

According to the American reports, the Cremona guards had released the smokescreen just after the end of the attak. (20) Moreover, the Axis troops had released, on other attacked secondary bridges, other smokescreens which had not been effective because of the wind. (21)

Still on that afternoon, the 340th Bombardment Group flew another attack over the Ferrara Railway Bridge, ‘a repeat of the morning’s mission’. (22) The American 12th Air Force considered Ferrara an important target, which was defended by the German Flak.

Meanwhile, the 15th Air Force B-24 heavy bombers attacked the port at Fiume/Rijeka, oil storage facilities at Trieste/Triest/Trst and Porto Marghera, and marshalling yards at four locations. At the same time, the 15th Air Force B-17 Flying Fortresses attacked a marshalling yard and railway bridges at three other locations.

An ordinary day of bombings on the Po Valley.

Almost immediately after this bombing, at 6:53 p.m., another wave of B-26 American aircrafts (319th Bombardment Group), led by Colonel J. R. Holzapple, dropped 143 bombs on the Cremona railways bridge, which was clear of smoke. (17) The target was hit and severely damaged, but not destroyed. (18) Consequently, Colonel Holzapple ordered a return the next day to make sure the objective was destroyed. (19) The 319th Bombardment Group’s policy was now to revisit a target repeteadly until when the objective was totally destroyed.

According to the American reports, the Cremona guards had released the smokescreen just after the end of the attak. (20) Moreover, the Axis troops had released, on other attacked secondary bridges, other smokescreens which had not been effective because of the wind. (21)

Still on that afternoon, the 340th Bombardment Group flew another attack over the Ferrara Railway Bridge, ‘a repeat of the morning’s mission’. (22) The American 12th Air Force considered Ferrara an important target, which was defended by the German Flak.

Meanwhile, the 15th Air Force B-24 heavy bombers attacked the port at Fiume/Rijeka, oil storage facilities at Trieste/Triest/Trst and Porto Marghera, and marshalling yards at four locations. At the same time, the 15th Air Force B-17 Flying Fortresses attacked a marshalling yard and railway bridges at three other locations.

An ordinary day of bombings on the Po Valley.

Note

1)Kroener, Bernhard R.; Müller, Rolf-Dieter, Umbreit, Hans, Germany and the Second World War, Volume V/II, Organization and Mobilization in the German Sphere of Power (Clarendon Press, 2003), p. 288; cf Veselý, Jirí Maria, Staudek, Frantisek, La resistenza cecoslovacca in Italia 1944/45 (Editoriale Jaca Book, 1975), pp. 15, 30, 32;

2)Muñoz, Antonio J., Pavlović, Darko, Hitler’s Green Army: The German Order Police and Their European Auxiliaries, 1933-1945. Western Europe and Scandinavia (Europa Books, 2005), p. 42; Thomas, Nigel, Andrew, Stephen, German army 1939-45 (5): Western Front, 1941-43 (Osprey Publishing, 2000), p. 11; Pietra, Antonio, Guerriglia e Controguerriglia (ed. Gino Rossato, 1997), pp. 96-99; Littlejohn, David Foreign Legions of the Third Reich. Vol. 3: Albania, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Hungary and Yugoslavia (2nd Printing – October 1994), p. 23; Veselý, Staudek, op. cit., p. 31.

3)Veselý, Staudek, op. cit., p. 31.

4)Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa, Volume 4, Issue 1, (Bundesministerium für Vertriebene, 1953), p. 56; Muñoz, Pavlović, op. cit., p. 41; Littlejohn, op. cit., p. 23; Epstein, M., The Statesman’s Years Book; Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1945 (Springer, 2016), p. 831.

5)Mori, Roberto, Galeazzi, Lucia, Piacenza, una città nel tempo, Volume II (Piacenza: Tip.Le.Co., 1998).

6)Ibid.

7)Caccialanza, Roberto, I Ponti sul Po Dirimpetto a Piacenza 1801-2013, Fantigrafica, 2013; Mori, Galeazzi, op. cit.

8)Intelligence Narrative No, 276, Day Operation, 12 July 1944 (Headquarters 320th Bombardment Group M).

9)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944; Alberti, Agostino, Vailati, Deira, Obbiettivo Cremona, (Storia Militare, 2009), p. 10; Styling, Mark, B-26 Marauder Units Of The MTO (Osprey Publishing, 2008), p. 69.

10)Il Movimento di liberazione in Italia, Volume 25 (Istituto nazionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione in Italia, 1973), p. 788; Cavazzoli, Luigi, Guerra e Resistenza: Mantova, 1940-1945 (Mantua: Postumia, 1995), p. 788.

11)Guidorzi, Alberto, Storia dello zucchero (Sermdiana n. 3, March 2002), p. 10; Malvasi, Rino, Sermidesi vittime civili della seconda guerra mondiale (Sermdiana n. 4, April 2005), p. 2; Mantovani, Sirio, Zuccherificio 60 anni di lavoro…in abbandono da 27 (Sermdiana n. 6, June 2009), pp. 29-30.

12)Corporal Sebastian A. Buffa, War Diary of the 340th Bombardment Group, July 1944; F.I. Report – 340th Bomb Group, 12 July 1944; Declassified, EO12958, War Diary, 488 Bomb SQ, Mission # 1, NO. OF A/C: 12 B-25’w, 12 July 1944.

13)Alberti, Vailati, op. cit., pp. 7-9.

14)Ibid., p. 7.

15)Bernstein, Jonathan, P-47 Thunderbolts Units of the Twelfth Air Force, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012.

16)Intelligence Narrative No, 277, Day Operation, 12 July 1944 (Headquarters 320th Bombardment Group M).

17)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944.

18)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944; Alberti, Deira, 2009, p. 7; Styling, op. cit., p. 69.

19)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944; Styling, op. cit., p. 69.

20)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944.

21)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944.

22)Declassified, IAW EO12958, Corporal Sebastian A. Buffa, War Diary of the 340th Bombardment Group, July 1944.

2)Muñoz, Antonio J., Pavlović, Darko, Hitler’s Green Army: The German Order Police and Their European Auxiliaries, 1933-1945. Western Europe and Scandinavia (Europa Books, 2005), p. 42; Thomas, Nigel, Andrew, Stephen, German army 1939-45 (5): Western Front, 1941-43 (Osprey Publishing, 2000), p. 11; Pietra, Antonio, Guerriglia e Controguerriglia (ed. Gino Rossato, 1997), pp. 96-99; Littlejohn, David Foreign Legions of the Third Reich. Vol. 3: Albania, Czechoslovakia, Greece, Hungary and Yugoslavia (2nd Printing – October 1994), p. 23; Veselý, Staudek, op. cit., p. 31.

3)Veselý, Staudek, op. cit., p. 31.

4)Dokumentation der Vertreibung der Deutschen aus Ost-Mitteleuropa, Volume 4, Issue 1, (Bundesministerium für Vertriebene, 1953), p. 56; Muñoz, Pavlović, op. cit., p. 41; Littlejohn, op. cit., p. 23; Epstein, M., The Statesman’s Years Book; Statistical and Historical Annual of the States of the World for the Year 1945 (Springer, 2016), p. 831.

5)Mori, Roberto, Galeazzi, Lucia, Piacenza, una città nel tempo, Volume II (Piacenza: Tip.Le.Co., 1998).

6)Ibid.

7)Caccialanza, Roberto, I Ponti sul Po Dirimpetto a Piacenza 1801-2013, Fantigrafica, 2013; Mori, Galeazzi, op. cit.

8)Intelligence Narrative No, 276, Day Operation, 12 July 1944 (Headquarters 320th Bombardment Group M).

9)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944; Alberti, Agostino, Vailati, Deira, Obbiettivo Cremona, (Storia Militare, 2009), p. 10; Styling, Mark, B-26 Marauder Units Of The MTO (Osprey Publishing, 2008), p. 69.

10)Il Movimento di liberazione in Italia, Volume 25 (Istituto nazionale per la storia del movimento di liberazione in Italia, 1973), p. 788; Cavazzoli, Luigi, Guerra e Resistenza: Mantova, 1940-1945 (Mantua: Postumia, 1995), p. 788.

11)Guidorzi, Alberto, Storia dello zucchero (Sermdiana n. 3, March 2002), p. 10; Malvasi, Rino, Sermidesi vittime civili della seconda guerra mondiale (Sermdiana n. 4, April 2005), p. 2; Mantovani, Sirio, Zuccherificio 60 anni di lavoro…in abbandono da 27 (Sermdiana n. 6, June 2009), pp. 29-30.

12)Corporal Sebastian A. Buffa, War Diary of the 340th Bombardment Group, July 1944; F.I. Report – 340th Bomb Group, 12 July 1944; Declassified, EO12958, War Diary, 488 Bomb SQ, Mission # 1, NO. OF A/C: 12 B-25’w, 12 July 1944.

13)Alberti, Vailati, op. cit., pp. 7-9.

14)Ibid., p. 7.

15)Bernstein, Jonathan, P-47 Thunderbolts Units of the Twelfth Air Force, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2012.

16)Intelligence Narrative No, 277, Day Operation, 12 July 1944 (Headquarters 320th Bombardment Group M).

17)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944.

18)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944; Alberti, Deira, 2009, p. 7; Styling, op. cit., p. 69.

19)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944; Styling, op. cit., p. 69.

20)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944.

21)Declassified, IAW EO12958, War Diary, 319 Bombardment Group, July 1944.

22)Declassified, IAW EO12958, Corporal Sebastian A. Buffa, War Diary of the 340th Bombardment Group, July 1944.